Yhdessä (Together). Inclusion and Friendship in Finnish Schools

J-PAL Photo Project

Originally published on the J-PAL website here

As global migration increases due to war, economic instability, and climate change, cities like Helsinki are becoming more diverse, with nearly one in five residents now speaking a foreign language at home. This shift brings both richness and challenges, especially for children of immigrants navigating questions of identity in schools.

The Kytke program, led by Finnish NGO Walter, addresses these issues through workshops that connect students with diverse mentors to promote dialogue around inclusion and discrimination.

Taken in Helsinki in March 2024, this photo series captures the Kytke workshops in action, highlighting moments of interaction between students and mentors. The project is currently being evaluated by researchers from Harvard University and Aalto University as part of an impact evaluation funded by J-PAL -- a global research and policy lab co-founded by Nobel Prize laureates. Full story and pictures in the J-PAL website.

The journey of an impact evaluation project.

Socio-economic integration of refugees in Uganda

This photo story takes you through the journey of a Randomised Controlled Trial (RCT) we carried out in Uganda, from its early design and planning stages, through the implementation of the intervention, to its final impact.

Our evaluation focused on supporting urban refugees by officially certifying their professional skills and matching them with local firms for short-term work internships. We set out to understand whether this type of programme could improve employment outcomes for refugees, shift firms’ attitudes and willingness to hire refugees in the future, and promote social cohesion between refugees and host community members.

All photographs and video were captured by Mariajose Silva-Vargas, one of the researchers behind the project and photographer. The full papers and authors can be found here.

Our evaluation focused on supporting urban refugees by officially certifying their professional skills and matching them with local firms for short-term work internships. We set out to understand whether this type of programme could improve employment outcomes for refugees, shift firms’ attitudes and willingness to hire refugees in the future, and promote social cohesion between refugees and host community members.

All photographs and video were captured by Mariajose Silva-Vargas, one of the researchers behind the project and photographer. The full papers and authors can be found here.

Phase 1: The Planning

Nakivale Refugee Settlement, 2019

Our first step in designing the study was to understand the diverse experiences of refugees in Uganda, especially the differences between those living in rural settlements and those in cities. Refugees in settlements like Nakivale often have access to a piece of land and basic services, but are isolated from economic networks and mobility. In contrast, urban refugees face challenges around informality, legal barriers, and social discrimination.

During an early scoping visit to Nakivale, we met individuals and organisations who had developed self-reliant livelihoods through farming, trading, and craftwork like Adonis from YAREN. While many had built strong economic networks within the settlement, they remained disconnected from formal employment systems, and few local firms operated in or near the area. These visits helped us gain a deeper understanding of the wider landscape of refugee livelihoods in Uganda. Given our limited budget (a common constraint for project implementers) we had to concentrate our efforts in one specific geographic area. We chose to focus on urban settings like Kampala, where we believed our labour market intervention could have a more immediate and scalable impact.

From there, we moved into deeper design and preparation. We conducted focus group discussions, collected descriptive data, and identified key constraints that our intervention could address. Crucially, we collaborated with refugee-led organisations in Kampala such as Young African Refugees for Integral Development (YARID) and Bondeko Refugee Livelihoods Center. Their deep understanding of the refugee experience and the communities they serve helped us shape a programme that was not only feasible, but meaningful.

From there, we moved into deeper design and preparation. We conducted focus group discussions, collected descriptive data, and identified key constraints that our intervention could address. Crucially, we collaborated with refugee-led organisations in Kampala such as Young African Refugees for Integral Development (YARID) and Bondeko Refugee Livelihoods Center. Their deep understanding of the refugee experience and the communities they serve helped us shape a programme that was not only feasible, but meaningful.

Paul (left), founder of Bondeko, and Elvis, a Ugandan team member, partnered with the research team during the RCT design phase. Their local knowledge was vital to shaping a refugee-led employment intervention

In particular, our work with Bondeko, an organisation founded by Paul Kithima, a refugee from the Democratic Republic of Congo, helped us build strong community ties. Bondeko supports refugees through initiatives such as urban farming, crafts, and energy production, and actively promotes social cohesion between refugees and Ugandan host communities. With input from Paul and Elvis Zani, a Ugandan member of the team, we designed the evaluation and recruited participants in ways that reflected the lived realities of the people we hoped to reach.

Our partnership with Bondeko and YARID directly inspired the intervention itself. Their work across both refugee and host communities showed us the potential of combining economic inclusion with social cohesion. Bondeko’s story is also featured in the short documentary we shot during our time with them.

Our partnership with Bondeko and YARID directly inspired the intervention itself. Their work across both refugee and host communities showed us the potential of combining economic inclusion with social cohesion. Bondeko’s story is also featured in the short documentary we shot during our time with them.

Bondeko’s story is also featured in this short documentary that we shot as part of our research project

Phase 2: The Intervention Design

Following the planning phase, we focused on a set of labour market challenges that many refugees face: limited access to formal employment, difficulty connecting with employers, and the lack of credible and certifiable ways to demonstrate their skills.

As part of our intervention, we invited refugee workers to take part in a formal certification process for their existing professional skills. In April 2021, a total of 977 participants were invited to sit for practical exams administered by the Directorate of Industrial Training (DIT) of the Ugandan Government, in collaboration with a vocational institute in Kampala.

As part of our intervention, we invited refugee workers to take part in a formal certification process for their existing professional skills. In April 2021, a total of 977 participants were invited to sit for practical exams administered by the Directorate of Industrial Training (DIT) of the Ugandan Government, in collaboration with a vocational institute in Kampala.

As part of the intervention, refugees undertook formal skills tests, like the participants posing in the picture, who took a cooking exam

These exams assessed hands-on skills specific to each trade: hairdressers were asked to style a client’s hair, chefs cooked traditional dishes such as beef stew, and tailors sewed garments like short-sleeved shirts.

More details on the cooking skills test

After certification, we randomly selected a group of certified refugees to take part in a one-week internship with local firms. This random assignment allowed us to rigorously compare outcomes between those who received internships and those who did not, giving us a clear picture of the programme’s impact, before scaling up.

![]()

![]() Participants during the hairdressing skills test

Participants during the hairdressing skills test

Phase 3: The Impact

In our results, we found that even a brief, one-week internship could significantly shift employers’ hiring decisions and attitudes. Firms that hosted refugee interns became more than twice as likely to hire refugees in the future, and many reported more positive perceptions of refugee workers.

We also explored whether workplace contact could improve social cohesion. We found that after working together, both refugee and Ugandan employees reduced their explicit biases toward one another. Moreover, both groups became more open to economic collaboration, though in different ways: Ugandan workers expressed greater interest in having refugee business partners, while refugees became more willing to work for Ugandan firms.

We also explored whether workplace contact could improve social cohesion. We found that after working together, both refugee and Ugandan employees reduced their explicit biases toward one another. Moreover, both groups became more open to economic collaboration, though in different ways: Ugandan workers expressed greater interest in having refugee business partners, while refugees became more willing to work for Ugandan firms.

The story highlights one personal story that illustrates the impact of the programme. Sifa, a refugee, was randomly placed at an internship with “Mama Prince,” a hair salon in Kampala owned by Mariam. That short placement turned into a lasting partnership. Sifa continued working at the salon long after the programme ended.

A quiet but powerful example of what becomes possible when barriers are removed and opportunities shared.

A quiet but powerful example of what becomes possible when barriers are removed and opportunities shared.

***

This photo story was shown at Collège de France in Paris, 22-23 June 2023, within the conference: "Science and the Fight against Poverty: How Far Have We Come in 20 Years and What's Next?" hosted by J-PAL Europe.

***

The research project was co-authored with Francesco Loiacono. It was funded by JPAL Jobs Opportunity Initative, IPA’s Peace & Recovery Fund, PEDL, SurveyCTO, the Mannerfelt and the Siamon Foundations. The full papers and authors can be found here.

︎: marijo.silva.vargas

Some behind-the-scenes at Bondeko

Nakivale Refugee Settlement and its settlers

Uganda, May 2019

Uganda’s refugee policy is praised worldwide

as it is different from other hosting countries: refugees can stay in settlements or they can decide to move to a city. In both cases, they can seek employment anywhere. Yet, only in the first scenario they receive humanitarian assistance and a piece of land to farm.

Promise Hub amphitheatre - Nakivale

Nakivale refugee settlement, approximately 200 km away from Kampala, is one of the oldest settlements in the country. It currently hosts 119,587 refugees from the Democratic Republic of Congo, Burundi, Somalia, Rwanda, Ethiopia, Eritrea (and others). Although many refugees in the area have been living there for several years, recent conflicts in nearby countries are increasing the number of arrivals per day.

At Kee Bar, a restaurant run by Ethiopian Refugees, with Adonis Mushongole Muganuzi

In May 2019, as part of my PhD research project on refugee youth integration in the Ugandan labour market, my colleague, our research team and I stayed in Nakivale for a week to collect data. During this time, we collaborated with several leaders within the settlement. One of them was Adonis Mushongole Muganuzi, the founder of YAREN – the Young African Refugees Entrepreneurs Network - an organization whose purpose is to give skills to refugees, focusing on leadership, entrepreneurship and behavioural change.

When asked about aid and land in the settlement, the leaders have little doubt: aid is often not enough, land is frequently far or un-productive, and the closest training centre - funded by the UNHCR and other governmental agencies - is 1 hour away by foot from the settlement.

Ahmed Dahir, a Somali leader in Nakivale

While in the settlement, Adonis from YAREN asked our team to give a training. We agreed to talk about excel and budgeting. On the training day we saw many participants from different grassroots organisations that wanted to learn more about funding and budgeting for their own enterprises.

During this event we realised that within the settlement there are many small grassroots organisations that focus on promoting entrepreneurship and empowerment between refugees. Even if they are all part of the same network, they remain independent and sometimes small.

During this event we realised that within the settlement there are many small grassroots organisations that focus on promoting entrepreneurship and empowerment between refugees. Even if they are all part of the same network, they remain independent and sometimes small.

Computer and budgeting training

Apart from the training’s participants, we also met members of Opportunigee and Promise Hub. These are self-organized empowerment and social entrepreneurship hubs formed by young scholars. Their main purpose is to generate digitally-enabled businesses that create jobs on a local scale and impact on a global scale.

Scholar of Opportunigee

These hubs want to link Nakivale’s entrepreneurs to the international market. They provide them with tools and resources to use the internet and to connect with companies such as DHL. Just last month, Promise Hub inaugurated their sustainable headquearters in Nakivale: a residence built entirely with plastic bottles.

Promise Hub headquarters built with plastic bottles

So, why so many grassroots organisations and why they promote entrepreneurship so much? The first answer is lack of jobs inside the settlement. Although Nakivale has been described as a full economy, survey data we collected plus extensive qualitative interviews seem to contradict this view (more on our research project soon).

Another important reason is that Nakivale is quite isolated from nearest towns, and transportation costs are high. Plus, lack of connections with the national labour market and information on how it works, limit refugees from looking jobs outside the settlement, even if the policy allows them to do so.

A Somali hotel re-using the UNHCR tents as walls.

We left the settlement with many questions but one certainty: governmental agencies and international organisations that are in charge of the refugee response in Uganda should go to these settlements, sit with these leaders and organisations and listen to their suggestions. They know what is happening inside the settlements and what could be done to improve them.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

All the people portrayed in these pictures have given consent to be published online

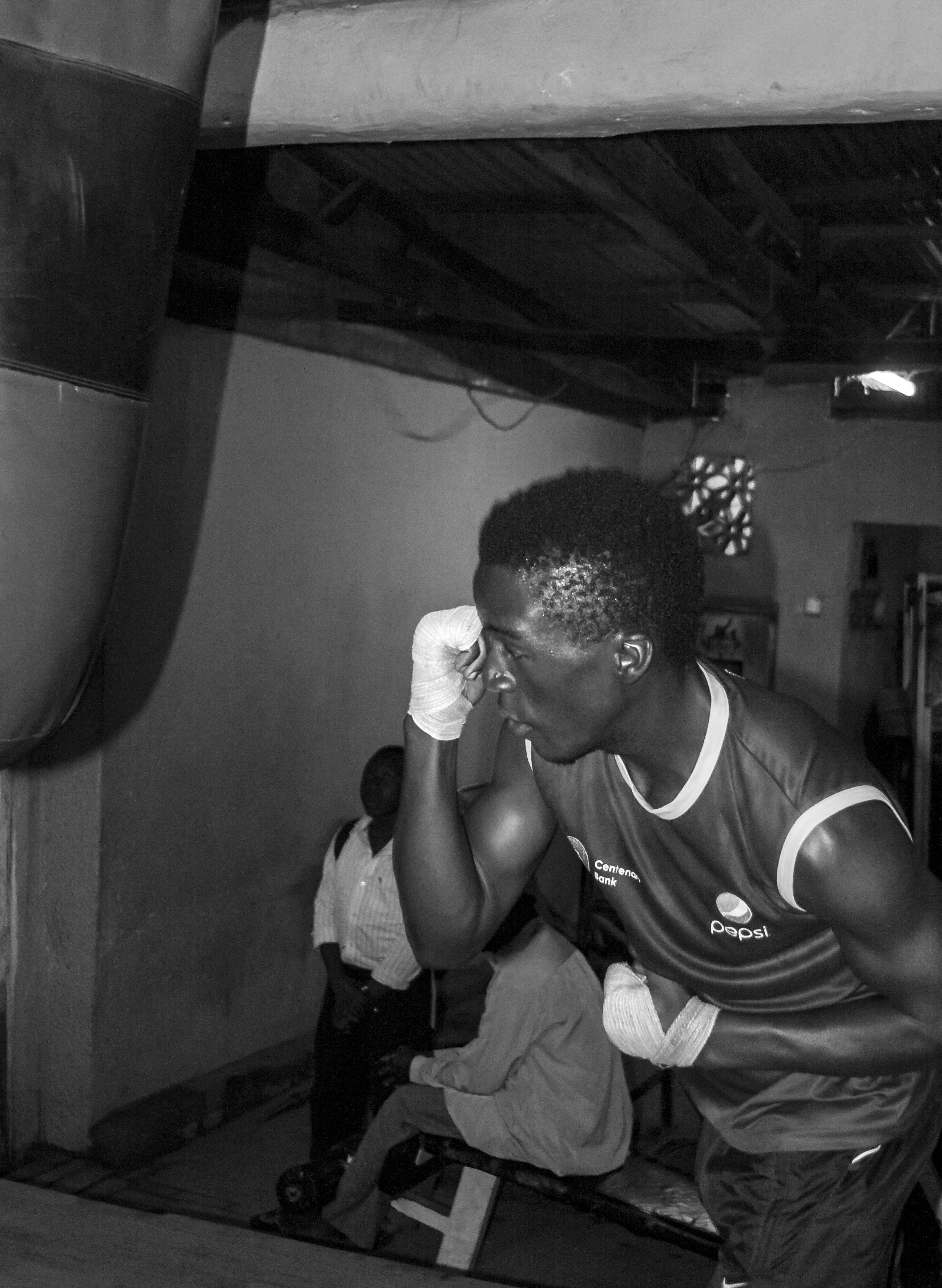

East Coast - Naguru Boxing Club

Entering from the brand new gate, the small slope of rocks and dust falls not too gently to the house of Hassan Khalil, the head coach, "baaba" (father in Luganda) in the slum of Naguru, north-west of Kampala, the capital of Uganda. Attached to the house, modest, there is the gym, old, small too, but full of energy.

Hassan Khalil, "baaba"

Feel the rope faster and faster whipping the old parquet, where wood sometimes falls under the feet of the athlete. Nassir, among the champions at the National Open Boxing (prelude to the Olympics) jumps faster in front of the broken mirror that covers one of the walls of the gym.

Nassir's training

Sweat leaves a brilliant track on Mohammed’s muscles, while coaching the "bazungu" (white people) mad about this sport. Meanwhile Miro - who is grandson to Hassan’s twin brother, Hussein - crashes his punches against one of the consumed boxing bags, which hangs from the beam fixed with rusty screws at the gym's entrance.

Miro

At the same time, Hakim teaches the basic movements to the many foreigners in Kampala, lovers of the freedom and flexibility of this sport (there are around 40 non-Ugandans who train regularly every week).

Albert and Charles are sparring with other kids from the slum, while Farouk and Timo alternate with Shadir, who dodges and hits fast while preparing for the next fight. Kassim, down the hall, with its slender, incredibly strong and firm arms, keeps his pads high, while a Canadian girl and a Ugandan one exchange their positions among jebs and rights.

Albert and Charles are sparring with other kids from the slum, while Farouk and Timo alternate with Shadir, who dodges and hits fast while preparing for the next fight. Kassim, down the hall, with its slender, incredibly strong and firm arms, keeps his pads high, while a Canadian girl and a Ugandan one exchange their positions among jebs and rights.

Founded fourteen years ago, the gym serves as a reference point for the Naguru slum, where Hassan trains youth and adults. The youngest is 7 years old and the oldest is 60. Hassan himself is almost 60 years old and has more than 170 fights "I've never been afraid in a fight - even if they tell me to face the world's champion, I'll jump in with no fear".

On the rickety wooden benches, where the athletes rest after each round, under a dreamy and focused young Muhammad Ali’s poster, the coach remembers old times when it was extremely dangerous to walk around at night in the neighborhood.

The East Coast Naguru Boxing Club is now more than an institution in the slum (if you ask to Naguru boda (motorcycles) drivers: "do you know where the East Coast Boxing Club gym is?" – you will get it right away, "of course, right in front of the mosque"). It is an anchor and a lighthouse of hope. Hassan lists the improvements he has planned to bring: with 4 million Ugandan shillings (approximately 1000 euro) he can enlarge the gym, build a new entrance and have a larger space for the ring where every two months amateur fights are organized, to convey passion among boys and girls in the slum and also to raise funds for the activities of the gym.

East Coast vs Ugandan Police

Hassan looks at his athletes as to his children. Between a workout and another, he teaches little ones (and especially the older kids) how to behave, to channel their energies in boxing gloves instead of in street violence and especially teaches a job to those who have finished studying (or that cannot afford to study).

Indeed Hassan started a few years ago to involve professionals in various fields (such as carpentry) and added to the gym also a sort of vocational school, where young people can learn a job. The only obstacle is finding enough teachers who can support the project. But "baaba" is a volcano of initiatives: many professional boxing schools pick among his best athletes. However, Hassan does not want to simply be a basic school, he also wants his medals. Hence, the idea of building a gym for very young professionals, and Hassan will start the construction of a new boxing club at Namboole area, close to the national football stadium.

Between prayers and gloves, Hassan’s life revolves around Naguru: "Why are you doing this, coach?", Hassan does not hesitate for a second: "There's too much poverty. I've always lived here, where my father’s mission was to give hope to the children of the slum. For everyone, his name was "baaba". Now "baaba" is me, it is my mission to these guys."

And the guys respond with heads full of dreams. Miro, Charles and Farouk (who are all less than 23 years old) are staring at the future and dreaming of becoming professionals in ten years

Albert, among the oldest and more expert athletes (28 years old) champs at the bit and cannot wait to jump to a higher rank. Hakim, among the youngest, dreams of returning to school. But everyone agrees on one thing: "The lessons of these teachers are invaluable. The freedom and the love for the sport that this gym expresses are invaluable."

And everyone knows at least one person who managed to get out of the degradation and delinquency thanks to the teachings of the Khalil brothers. And some have even regained confidence in life after a tragedy: the story of Bashir Ramathan, the blind boxer, has been reported by the New York Times a few years ago.

Prayers and gloves. Hassan, in the morning, calls the prayer from the mosque in front of his house. After that, he calls everyone to the gym, ready to teach how to fight among rocks and dust.

Prayers and gloves. Hassan, in the morning, calls the prayer from the mosque in front of his house. After that, he calls everyone to the gym, ready to teach how to fight among rocks and dust.

*Written by Francesco Loiacono. Photo by Marijo Silva

The Ugandan Quidditch team: when reality overcomes magic

Article and photos by Marijo Silva

Some years ago, John Ssentamu read the first volume of J.K. Rowling’s work: Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone. He borrowed the book from a person he saw reading it while traveling on a matatu: a minibus licensed for carrying 14 people, and one of the most popular means of transportation in Uganda.

Players and their improvised broomsticks

After finishing the volume, following his curious mind and spirit, he searched on the Internet more information about the famous wizards’ game vividly described in the book: The Quidditch.

He was then flabbergasted and surprised to discover that the fantastic game was not only played in books and movies, but it was also a serious sport on Muggles’ earth. People from all over the world were jumping, running and holding broomsticks between their legs while playing with different balls in a soccer field. The Quidditch was so well established that even a world tournament was organized every 2 years.

John Ssentamu holding a broomstick and a "bludger" ball

During the same time, John was already questioning about ways to foster development in his hometown of Masaka district, a town two hours away from Kampala.

A Keeper between the hoops

“I was wondering how I could attract people’s attention into our region. A sport could be a way, but soccer, basketball, football…not an option! We could never be better than players in other Ugandan cities, where these sports were already famous and played by professionals. So what about Quidditch?! ” John candidly explained, during our trip in a matatu, traveling from Masaka’s center to one of the villages where the game is usually played.

And so, in 2013 John started his unusual and magic adventure involving several people in his community. They learned all the sport's rules from the Internet: by watching videos, reading articles and by posting questions to the Quidditch community, using the Ugandan Quidditch team’s Facebook page, which John himself opened.

John and one of the Quidditch teams in Uganda

Initially, they locally mobilized resources to acquire basic gear in order to start practicing in the field. Later, they received additional equipment from donors or “Friends of Quidditch” as John described them.

Quidditch's initial position

In 2014, their story reached professionals from the international Quidditch community in different parts of the world. The same year, for the first time, they welcomed a British fellow player who assisted them in specializing and improving their skills. Their perseverance and hard work made it legitimate to aspire to the highest of any sport achievements: participating in the 2016 World Cup in Germany.

The Ugandan team's main aspiration is to participate in a Quidditch World Cup

And so, in order to participate to the World Cup, the Ugandan Quidditch fellows had to face an impressive number of hurdles: they had to apply and receive approval from the International Quidditch Association to join the tournament; in absence of local resources, they started (and successfully achieved) a crowdfunding campaign to cover the costs of their trip to Germany; they applied and obtained passports for all the team players (not an easy task in Uganda). Only one very last step remained: the visa to enter Germany.

Players waiting for the next move

Unfortunately, they couldn’t get the needed approvals on time, as not all members of the team had access to a bank account, which is required by the German law: bank accounts in Uganda are still not a developed saving tool, especially because saving via “mobile money” is still the cheapest and most successful system used, above all in rural areas.

Nevertheless, John said it was just a first try. They expect to be prepared and ready to go for the next World Cup in 2018. At the same time, John keeps pushing nationally and internationally to promote Quidditch in Africa, especially because is a communitarian experience that does not discriminate by gender, since men and women can play together.

Quidditch is played by males and females together

“This is another beautiful thing about this game, it is something you can do together, whether you are a girl or a boy”. John’s enthusiasm was contagious, while we watched several kids playing together.

Watching the match

John’s efforts are giving their fruits: nowadays the team comprises 53 players: 36 are children and 17 are adults, in 4 different districts in the south of Kampala: Masaka, Kalangala, Wakiso and Sembabule.

"John, one last question, what do you think is a priority to make this game more popular in your country"

“First of all we need to put in place reliable sources of funding so that all our plans are achieved. We are thinking about some new income generating activities and we are searching for local and international sponsors to enable us to realize these plans".

Playing Quidditch is a communitarian activity

"We want to see Quidditch expanded to other schools and communities and we would like to create regional and national tournaments. Also, we are looking for an international team to visit us and train with us as part of 2018 World Cup’s preparations.”

John is challenging the world. Who knows, in the future, the Quidditch World Cup could shine under the Ugandan sky.

Follow this link to get in touch with Quidditch Uganda